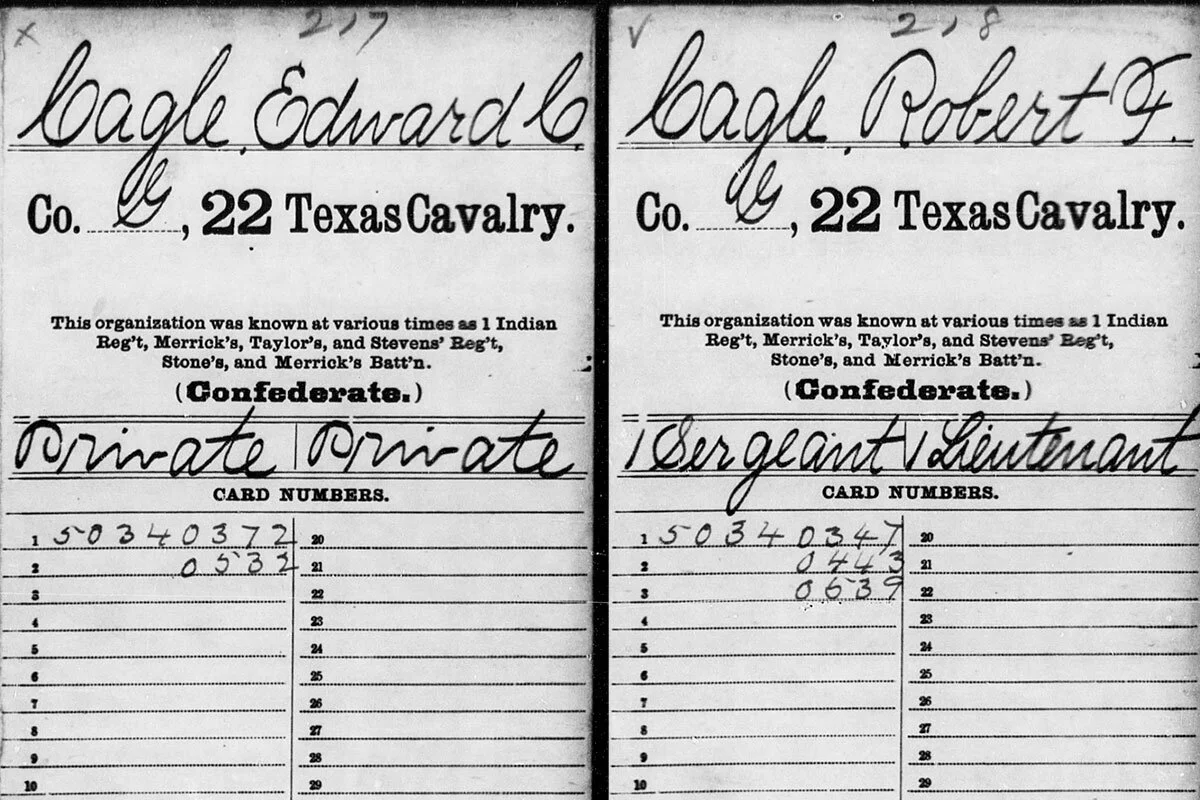

As reported in a previous post, I found confirmation of the deaths of Edward and Robert Cagle at a date prior to November, 1864, in the Fannin County Probate Minutes, Book E, page 421. Thomas C. Hale’s appearance before the Court on that date is documented there. He made a report to the court on his efforts to settle the estates of Susan C. Cagle, Edward C. Cagle, and Robert Cagle, and asked to be discharged of any further duties. Knowing that these Cagle boys had died young and without descendants provided some closure, but left many unanswered questions. On the advice of a fellow researcher, I turned to Laura Douglas, Special Collections Librarian at the Emily Fowler Library in Denton. Laura was my much appreciated guide into the rich world of Civil War military records. There I found true closure for Edward and Robert Cagle.

Edward & Robert pledged themselves to fight for the Confederate States by enlisting in the 22nd Texas Cavalry on Dec. 17, 1861 in Honey Grove, Texas. Edward was 19 years old, and is described in his military records as 5’ 10” tall, with fair complexion, light hair, and grey eyes. Robert was 24 years old, 5’ 8” tall, of dark hair and complexion, but sharing with his brother the trait of grey eyes. Both listed their occupation as ‘farmer’. The young men mustered in on Jan. 13, 1862, at Fort Washita, Oklahoma. They each came with their own horse and rigging, and the value was duly noted in their records. Edward mustered in as a private and Robert as a sergeant.

The 22nd Texas Cavalry was organized under Colonel Robert. H. Taylor and included recruits from Fannin, Grayson, Collin, and other North Texas counties. In July of 1862 the 22nd joined the 31st Texas and the 34th Texas to form a cavalry brigade. The combined troops saw their first engagement on Sept. 30, 1862 at Newtonia, Missouri in a successful skirmish against Union forces. Edward, however, did not see any of this. While the military records do not supply any detail, they do document his death at home in Fannin County on March 22, 1862. Robert’s military career did not long outlast his brother’s. He also died prior to the brigade’s first action, succumbing to accident or disease on August 24, 1862, at Ft. Gibson, Okla.

After their early success at Newtonia, the troops fell back into Arkansas where illness, changes in command, and reclassification from cavalry to infantry demoralized the men. The Handbook of Texas Online states that the struggling troops fought as a “dismounted cavalry” at Prairie Grove, Arkansas on December 7, 1862, before moving to Ft. Smith in Jan., 1863, and then marching through snow to the Red River in Feb., 1863. Glory continued to elude the 22nd during the remaining years of the war. The surviving troop returned to Texas in March, 1865, where it was disbanded in May of that year.

Pages from the Fold3.com military records of Edward and Robert Cagle.

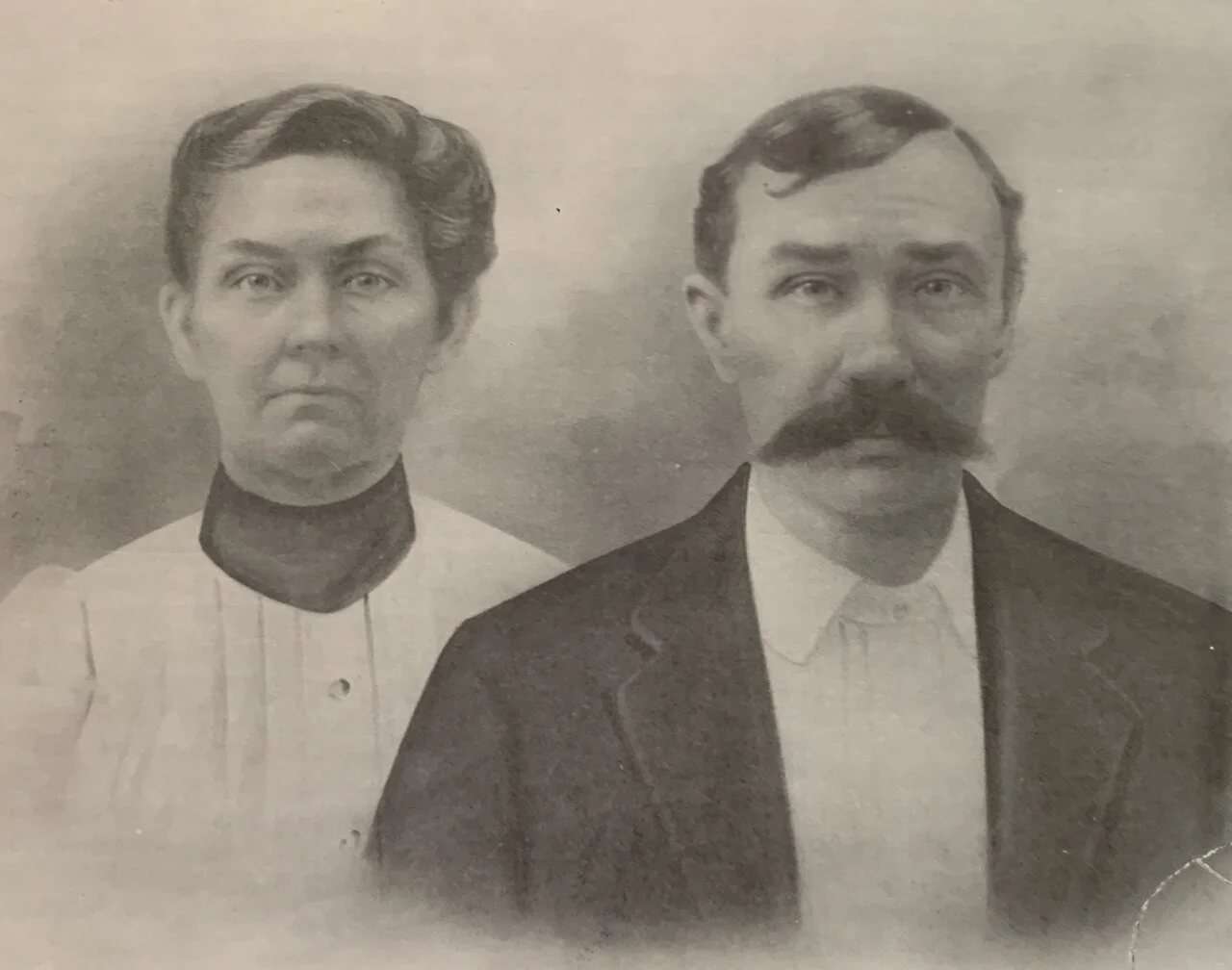

Based on this early success researching the Cagle family, I eagerly began seeking details on John Bonham’s Civil War history. His story proved more elusive. I had two references to work from. The first being a family history written by John’s granddaughter. Pine Cones and Cactus, by Eddie Gist Williams Addison (As told to Thelma Lacy), was published in 1980, at San Angelo, Texas. In it, the author states,

“My mama, Charity Josephine (called Tatty by the younger children) Bonham, was born in Arkansas on May 19, 1862. Her mother was Penelope Edward Boone, and her father was John Bonham. Grandma Penelope (Penny) was born in 1827 in Tennessee. Grandpa John was born in 1817 in North Carolina. Grandma’s parents were born in Tennessee and Grandpa’s in North Carolina.

Mama told me about living in Arkansas during Civil War days. She remembered when Grandpa rode off to fight for the South. She said he managed, somehow, to slip home and help with the planting in the spring and the harvesting in the fall and then make his way back to the front lines, leaving Grandma and the children and a few slaves to manage the big farm.

She remembered when he came back after the defeat of the Confederate troops, battered and beat - with nothing left to do but pull up stakes and move on to another place, another beginning.”

The problem with this recollection is that Tatty could have been no more than an infant when her father enlisted in the Confederate Army, as she was only 3 when the war ended. It seems likely that she related family stories to her daughter, not her personal memories. In any case, the account provides an evocative glimpse of how the War affected the Bonham family.

The second reference I had was an article in The Bonham News (Vol. 44, No. 100, Ed. 1, Tuesday, April 12, 1910), found on The Portal to Texas History. In the column, Observations by the Way, Ashley Evans recounts a visit with John Bonham, stating,

“…Stopped first at John Bonham’s. He is 88 years old. He wore the grey four years and was with Shelby. At the close of the war he cast his lot with the good people of this county.”

Despite these tantalizing tidbits, I found nothing in the official military records that I could definitively attribute to ‘our’ John Bonham. I had hoped the Muster Rolls might provide a fix on when his service to the Confederacy ended, thus providing a more defined window for the migration of the family from Arkansas to Fannin County, Texas. That hope was disappointed and will have to wait for another day.

Charity Josephine (Tatty) and John Posey Gist, from Pine Cones and Cactus.

Turning to the Wilks family, I was able to find the service records of eldest son, Jefferson Wilks (the younger sons were children during the war). He was a member of the Union Army, serving in Company E of the 30th Regiment of the Iowa Infantry. He began his military career as a private and ended as a sergeant. The Regiment was mustered in on Sept., 20, 1862, and served in a number of distinguished campaigns, including the siege of Vicksburg, the battle of Lookout Mountain, and the battle of Missionary Ridge, prior to marching to the relief of Knoxville on Nov. 28, 1863. In Dec., 1863, the Regiment was assigned garrison duty in Alabama, an assignment that lasted until late spring of 1864. Jefferson Wilks died on April 10, 1864 in Claysville, Alabama at the age of 23 or 24.

Find-A-Grave provides the following information about Jefferson,

“Killed in action April 10, 1864, Claysville, Ala. … Would have been buried close to death site. Then possibly moved to a national cemetery as an unknown abt 1867.”

I have not been able to find confirmation in the military records of Jefferson dying in action. Nor have I found a record of a battle corresponding to the date and location of his death, so I have some reservations about the accuracy of this report. However, Claysville, Alabama was a strategic location due to the ferry there across the Tennessee River. It is possible that Jefferson died in a skirmish defending the ferry. It is also possible that Jefferson died of disease. Within the Regiment, eight officers and 65 enlisted men were killed in battle or mortally wounded during the course of the war. Three officers and 241 enlisted men were lost to disease (https://military.wikia.org/wiki/30th_Iowa_Volunteer_Infantry_Regiment). This sad statistic speaks volumes to the conditions the enlisted men suffered outside the immediate threat of battle.

Union Cavalry Camp, Library of Congress.

Story by Wanda Holmes Oliver.