In the weeks since my last post, I have retired from my profession and found myself busier than ever adjusting to my ‘life of leisure’. My work on this project has been interrupted and my New Year’s pledge is to pick up the threads and move forward with it again. While I have new research to organize and plenty of research yet to do, a good place to reengage, I think, is to share some research already completed about the life of Milton Wilks.

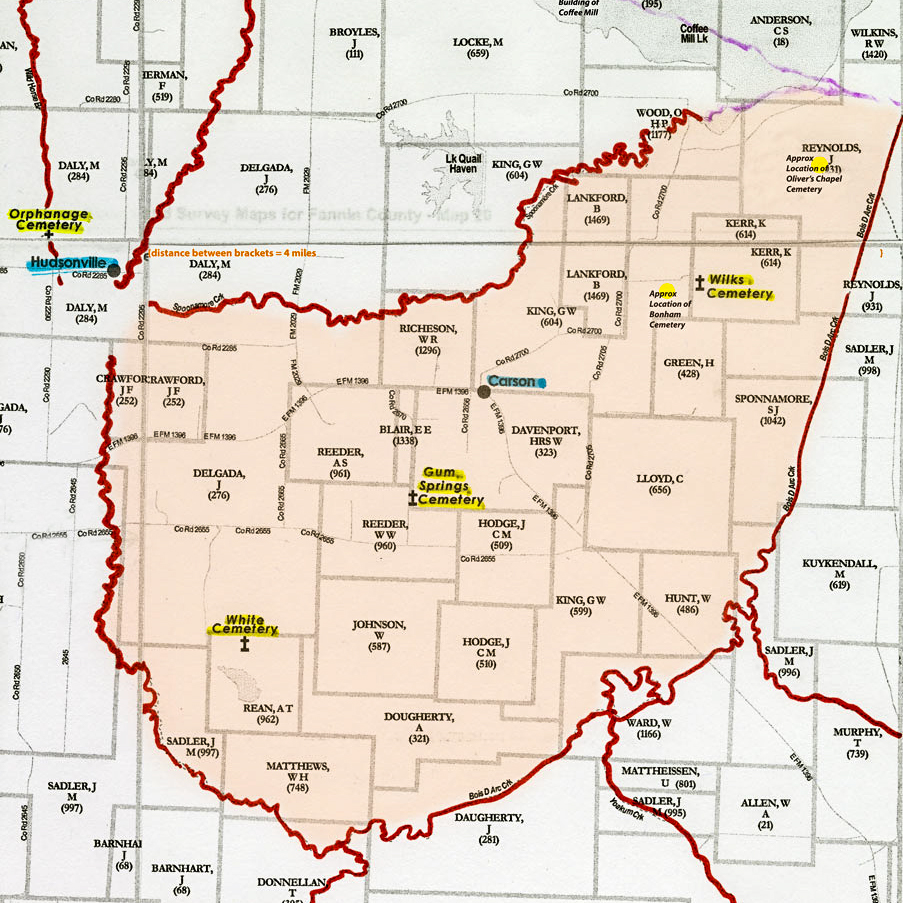

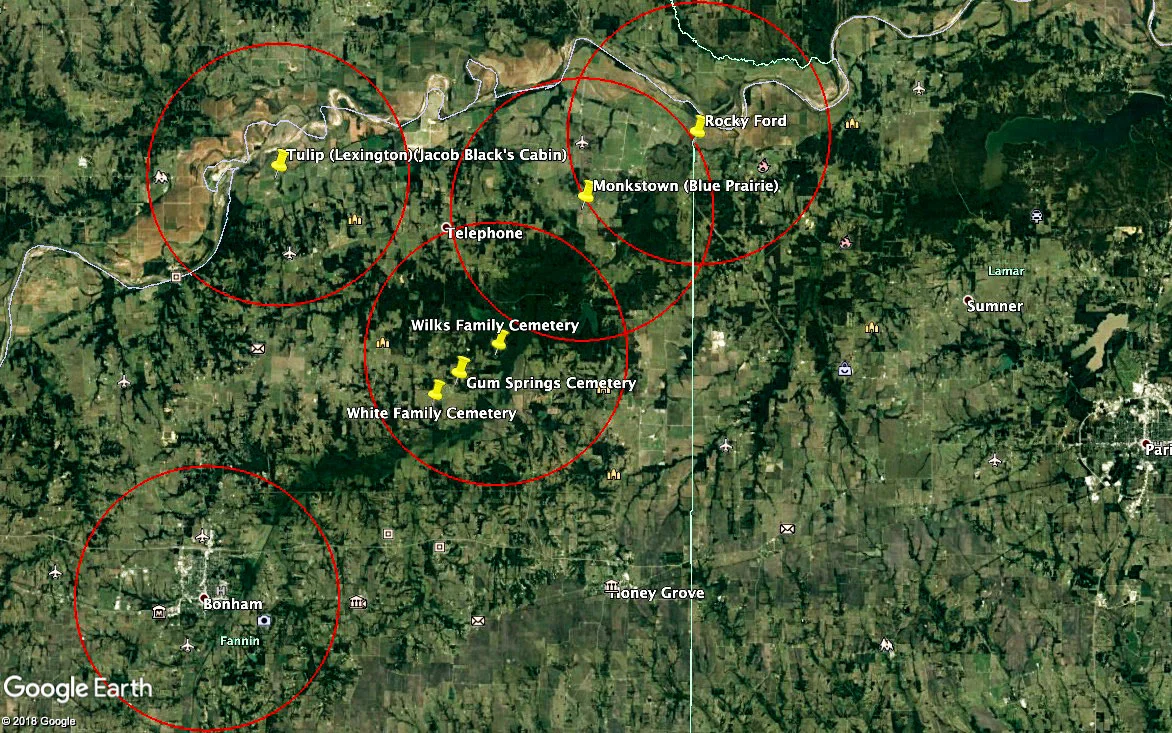

When Milton died on August 8, 1927, he was not the last of his generation - his sister-in-law, Mary Wilks, wife of brother Newton Wilks, would live until 1932 and sister, Rebecca Wilks White would live until 1940 - but the details we have of his life provide fitting bookends for the beginning and ending of an era. Milton arrived in Texas in 1865 or 1866 with his parents and four of his siblings. He was the baby of the family and would have been nine in 1866. We have to believe that moving from Iowa to Texas in the aftermath of the Civil War had to figure as something of an adventure to a young boy, and northeast Fannin County something of a wild frontier. It had only been 30 years since Daniel Rowlett and his band of families had become the first permanent anglo settlers to make their homes west of Bois d’Arc Creek. The Treaty of Bird’s Fort ending hostilities with the Native Americans was only 23 years old at the time. At the other end of the spectrum, as Milton’s death approached, the industrialism and economic growth of the Roaring Twenties were drawing to a close. Cotton was King and Fannin County had seen years of booming agricultural production and wealth creation.

Eldest brother, Jefferson Wilks, died in 1864, a victim of the war, and though that death was no doubt deeply felt within the family, Milton, a child of six or seven, may have felt the loss less severely. And it must have been with great optimism that his parents left behind married daughters and grandchildren to make a new home in remote Texas. However bright the future had appeared when the family arrived in Fannin County, repeated loss would sadly mark Milton’s life. He was not quite 12 when his mother was laid to rest in 1869, and only 14 when his father joined her.

That the siblings remained close is evident in family correspondence (which can be seen here), and further corroborated by the purchase by the Wilks boys, Madison Solomon, Newton, and Milton, of the 214 acres containing the Wilks Cemetery in August of 1873 from the heirs of the Cagle estate. Milton was only 16 at the time, Newton 18, and Madison Solomon not yet 22. Again, they must have had high hopes and grand plans for their future as they made their investment. At $412 (approximately $8,800 today) the land was acquired at considerably less than the $535 it had been valued at in 1864 when the Cagle estate was settled. When the boys sold the land to George Buchanan in Oct, 1879 for $500 (just under $13,000 today), they realized a nice profit. Perhaps Milton’s good fortune set him up to pursue marriage as he became a married man the following year.

In November of 1880, at the age of 23, Milton married Betty Moore. He laid her to rest in January of 1887 just over six short years later. In those six years the two of them had buried 3 baby boys. Milton and their only surviving child, a son not yet 2, were left to grieve Betty’s passing.

In June of 1888, Milton married for the second time. His bride was Florence Ester French, a girl still a couple of months shy of her 16th birthday. With his young bride, Milton must have once again looked to the future with bright hope. Their first child, a daughter, was born in August of 1889 and buried that October. In January, 1898, they were graced with a second daughter who would live to adulthood, but in February of 1901, Milton would lose his wife, Florence, and his brother, Newton, within two weeks of one another. A widower for the second time, Milton had to bear up under the load of life with two children, Frank, not quite 16, and Winnie, barely three.

1908 would see the death of a granddaughter, tragically burned, and Milton’s third marriage. Milton and Raymond Bill Holiday Clark were married on November 18, 1908. Milton was 51, Raymond 47, and Winnie 10. Raymond was a widow with an 11 year old son. Just shy of ten years later, Milton was again left a widower, when Raymond died in September, 1918.

In August of 1920, Milton married for the 4th time. His bride was Mattie Cornelius Jones McConnell. Mattie was the widow of Ellis Thurston McConnell. At their marriage, Milton was 63, Mattie was 46. Mattie had several adult children and a young daughter of 10. In an interesting side note, George, son of Ellis and Mattie married Milton’s great-niece, the granddaughter of Rebecca Wilks White.

In July of 1927, Milton sat down to write his last will and testament, a document you can see here. It is easy to speculate that he felt his time drawing near as he died within a few weeks of the writing, on August 6, 1927, just shy of his and Mattie’s 7th wedding anniversary. His will reads to me as the testament of a stalwart and dutiful man, taking great care to leave his affairs in order and his loved ones sharing fairly in the estate he left behind.

The inventory of his estate lists $2,671.00 in separate property, and $661.00 in community property, for a total of $3,332.00. The equivalent in today’s dollars is just over $47,000.00.

From left to right, Julia, Milton, & Rebecca Wilks. Photo courtesy of Donald White.

Story by Wanda Oliver.