In the Wilks Cemetery there was a beautiful monument to the “Family of S. C. and M. G. Cagle”. Tall, monolithic, beautifully carved and inscribed all round, it marked what we came to term, “the Cagle Row”. To the north of the monument were four small foot stones with the initials, “MSC”, “SHH”, “ESC”, and “MVC”. To the south was a foot stone marked, “JHC”, for a total of seven expected graves. The disinterment revealed eight graves in this row, only two of which we could be certain about - the graves of Susan Catherine Barkley Cagle and Martin Gaines Cagle.

Rubbings from the Cagle monument.

Based on the inscription on the monument, the ready assumption was that the foot stones with initials ending in “C” were Cagle children. It also seemed certain that SHH, resting between MSC and ESC, was a family member. I set out early on to discover as much as I could about the Cagle family, and align the facts with the evidence in the Cemetery.

I was able to use familySearch.org to zero in on an 1850 census that seemed to establish the nuclear family as parents Martin and Susan, along with children Robert, Frances, Edward (or Edmond), Martin, and Mary. Then I discovered an entry in the 1850 Fannin County Mortality Index, that established the existence of little Martha, dead in Sep, 1850 of scarlet fever, and my definition of the family expanded.

In the 1860 census, Susan, age 44, Robert, age 23, Edward, age 19, Mary, age 13, and John, age 9, are listed. Martin Cagle (the senior) had died in 1852. I had found uncorroborated evidence that Martin (the son) died at age 16, placing his death in 1860, though he is not listed in the 1860 Fannin County Mortality Index. His absence from the census seemed to support an early death, perhaps earlier than 1860. Frances had married in 1956 which explains her absence. John was not yet born at the time of the 1850 census. His presence in the 1860 census led me to expand my definition of the family again. (As a side note, the 1860 census also includes Willis Escue, age 21, a farm hand.)

I worked for months with this family roster - Martin and Susan and seven children, mapping the family members onto the marked graves in the “Cagle row” with a sense of certainty. MSC and MVC I ascribed to Martha and son Martin. ESC and JHC I presumed to belong to Edward and John. SHH remained a mystery.

Then, months later, I found a memoir written by Frances Cagle’s husband, Thomas Hale, which stated, “…. To Mr. and Mrs. Cagle were born eight children: Frances, who is now Mrs. Hale; Robert; Edward; Martha, who died in childhood; John; Martin; Susan, deceased; and Mary, the wife of R. Russell.” My conception of the family had to expand again to include Susan, who must have entered and left this world in between census years. This bit of information had the advantage of providing closure in a reliable way - there were eight children, a fact confirmed by a close and contemporary family member, well after the death of the parents, Martin & Susan. The family roster was complete. However, I still had no information on little Susan other than the fact of her existence. And I had found almost nothing about the sons that appeared to reach manhood - Robert, Edward, and John.

Martin and Susan married in May, 1836. Robert was 12 years old in the 1850 census, placing his birth in 1838 or thereabouts. Frances was born in May, 1839. In the 1840 census for Lafayette, Arkansas, which does not list by name anyone other than Martin, the family consists of an adult male between the ages of 30 and 39, an adult female between the ages of 20-29, two children under the age of 5, and a female aged 15-19. The teenager is a mystery, but the adults correspond to what we know about Martin and Susan, and the two children to what we know of Robert & Frances. It is possible that daughter Susan was born in 1837 and died before the 1840 census was taken, however there is a user-submitted family tree on ancestry.com that places her birth in 1847. If this is Susan’s correct birth year, she presumably died in Fannin County, though we have no record of her death. If she had died in the same epidemic as Martha, surely she, too, would be listed in the 1850 Fannin County Mortality Index. Why is there no foot stone in the cemetery corresponding to her initials? Had she already been laid to rest when Little Martha died? Could she have been laid to rest elsewhere? It saddens me to think of the little sprite all but lost to history.

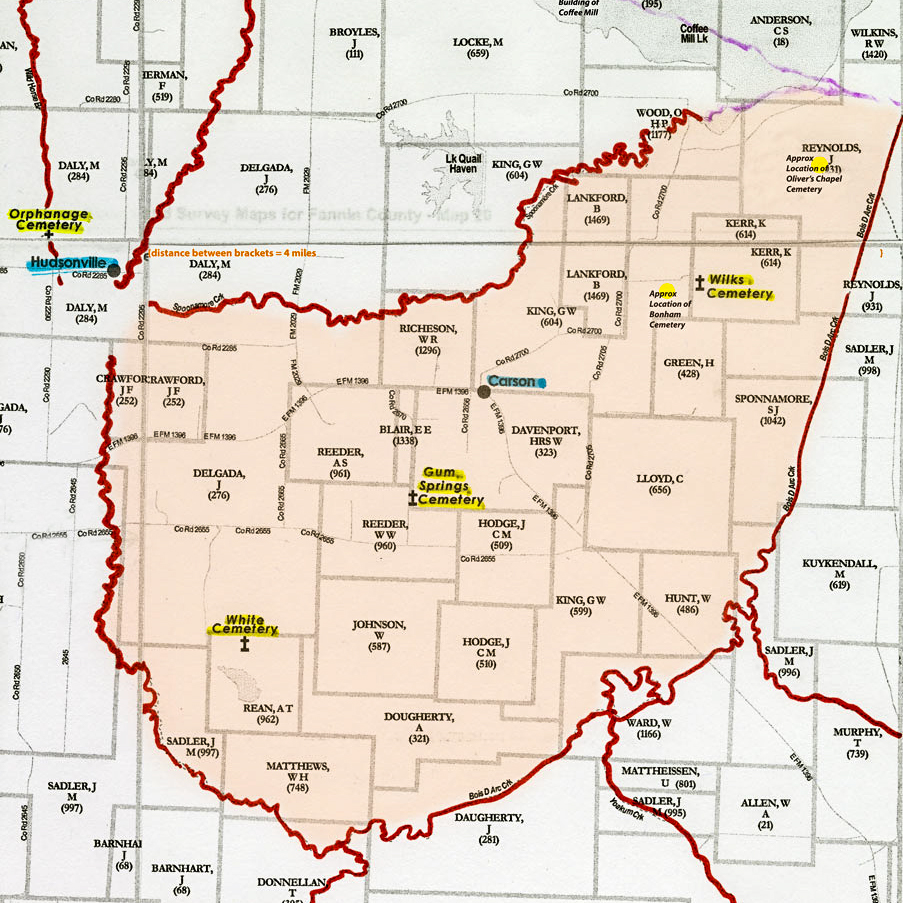

Tax records also provided valuable insight into the family circumstances. After Martin’s death in 1852, the records clearly show that Susan continued as head of household and might even have expanded the family holdings. The Fannin County tax rolls for 1857 show Susan assessed for 320 acres on the Sulphur River in addition to the 214 acre tract that held the Wilks Family Cemetery. The 1864 Tax Rolls list the tracts as “Cagle, Susan, by T. C. Hale, Admin”, indicating that the land is still held by the family despite Susan’s death in 1861. In 1865, both tracts are listed under Thomas C Hale.

This was the extent of my information when I began looking at the Fannin County Probate Minutes. In Book E of the Probate Minutes, page 260, there is an entry dated, November 24, 1862, which states

“Guardianship of the minors Mary C. Cagle and John H. Cagle. It is ordered by the court that Thomas C. Hale be appointed guardian of the persons and property of John H. Cagle and Mary C. Cagle ( the said Mary C. having chosen in open court the said Thomas C. Hale) and that he give Bond in the sum of $1000. One thousand dollars each and that letters issue.“

At the time of this entry, Mary Cagle would have been sixteen years old and John eleven. Then on page 421 of the same book, minutes dated November 28, 1864 address the settlement of the estates of Susan Cagle, Edward Cagle, and Robert Cagle. The entry reads in part

“Thomas C Hale the admin of the estate of Susan C. Cagle, Edward C. Cagle and Robert Cagle dec’d would file herewith his final report for a settlement of said estates and ask to be discharged from all further liability as admin. He states that there are but three heirs to the said estates viz Frances D. Hale the wife of this admin & the minors Mary C Cagle and John H Cagle.”

With this document we have confirmation of the deaths of Edward and Robert at some point prior to November, 1864, and a strong indication that they died without descendants, their siblings being their only heirs. The absence of any mention of son Martin, is a strong indication that he, indeed, died sometime prior to the death of his mother. Furthermore, we have confirmation that John H. Cagle is still living in late 1864.

In Book V, of the Deed Records, page 492, in an entry dated August 11, 1873, the sale of the 214 acres of the Wilks Cemetery tract by the Cagle heirs to Madison, Newton, and Milton Wilks is recorded. The signatories to this document are Thomas C. Hale, Frances D. (Cagle) Hale, R. F. Russell, and Mary C. (Cagle) Russell, leaving us to wonder still about the fate of young John. In 1873 John Cagle, if living, would have been a young man of 22. Does his absence as signatory to this deed indicate that he had died sometime between 1864 and 1873? Hoping to find more of his story I returned to the County Clerk’s Office to investigate the death records - records I had not yet dipped into. I went prepared to carefully search the death records from 1844 - 1873 - from a year prior to the date I believed the Cagles to have arrived in the area through the year of the sale of the Cagle property to the Wilks. I hoped to find more information about the deaths of the Cagle children. I hoped to find references to the burial place of Martin Gaines and Susan Catherine, a reference that might prove useful in understanding the history of what became the Wilks Cemetery. Sadly, what I found was that we do not have death records in Fannin County prior to 1903.

Regarding the foot stones in the Cemetery, the assumption that those with initials ending in “C” line up with children Martha, Martin, Edward, and John is not disputed by the facts, though the facts do not provide certain proof either. “SHH” is still a mystery - perhaps a member of the Hale family - and the unmarked grave even more obscure. Unless some unexpected breakthrough comes my way in my research, we will have to wait for what science and DNA can tell us.

There is an interesting side note that came out of this research. In the record of the transfer of the land to the Wilks, the document describes the property as

“…on Bois D’Arc Creek containing two hundred and fourteen acres less one fourth of an acre surveyed by virtue of the headright certificate of James Kerr…”.

I can’t help but wonder if that 1/4 acre exclusion is our cemetery, and whether that indicates that it was, in 1873, seen as a community cemetery rather than a family cemetery on private land.

Story by Wanda Holmes Oliver.