The overwhelming surprise when the Wilks and Bonham Cemeteries were disinterred was the number of unmarked graves found. What we had assumed to be the resting place of two well-marked families became a much more complicated situation. Like the Cagle family (see previous post) the outline of the Wilks family emerged early and seemed complete. But again, my assumptions were called into question.

With the exception of Mary Wilks, whose grave was marked only by a metal funeral home stake, the Wilks graves had lovely tombstones - richly decorated and graceful, with touching symbols of birds, lambs, twining ivy, and clasped hands. Each stone was also graced with loving sentiments carved in script. Mary died in 1932 and was presumably the last of the family to be buried in the cemetery. While her grave was not given a stone, it remains hard to imagine any prior Wilks burial remaining unmarked given the beautiful tombstones standing witness to a family who honored their dead with great care.

But there are mysteries to be solved in the Wilks family just as there are in the Cagle family. The information in the historical record poses questions and the three unmarked graves lying between the Wilks and Cagle rows (see schematic below) beg explanation. These graves could be from either family or from neither family. Only the results of the scientific assessment of the remains will provide true closure. In the meantime, we can work to develop educated guesses as to who these souls might be and the records do provide some possibilities.

Gray markers indicate the relative position of the unmarked graves found. Yellow markers indicate the Cagle row. Green markers indicate the Wilks row.

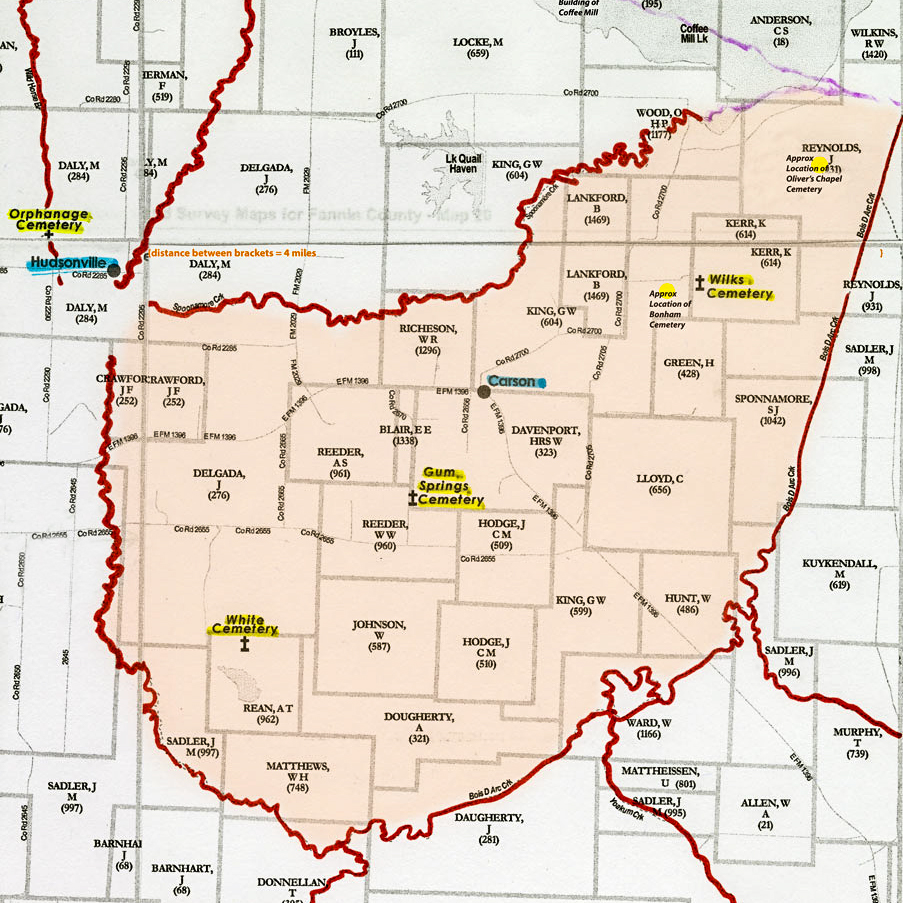

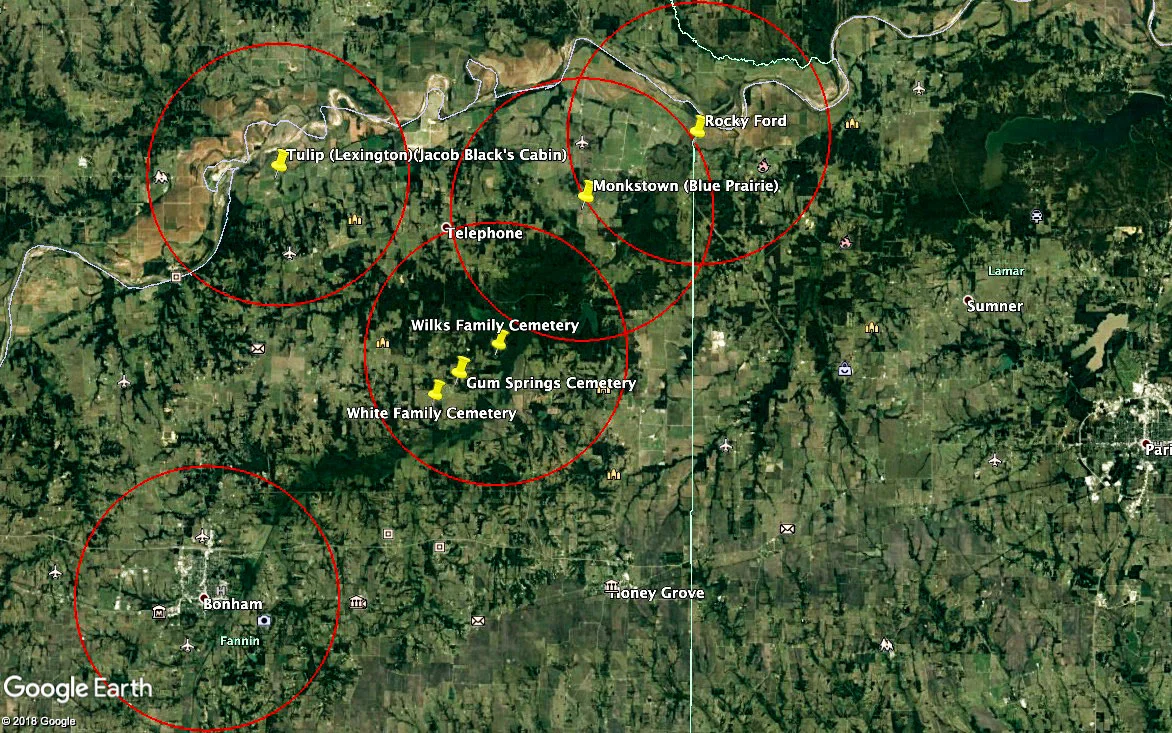

Though the Wilks family did not buy the Cagle farm from Susan and Martin Cagle’s heirs until 1873, clearly the Wilks developed some association to the farm or the immediate surrounding area soon after arriving in Fannin County in 1865 (see newspaper article here regarding Fannin County Old Settlers Association meeting in Dodd City, Texas on Aug. 1-2, 1917, in which Milton Wilks is listed as having arrived in Texas in 1865). Margaret Wilks was buried in the Wilks Cemetery in 1869 and Thomas Wilks joined her there in 1871. Perhaps the Wilks were tenants of the Cagle heirs. Perhaps the cemetery was already in use at the time of Margaret’s death as a community cemetery rather than a private family cemetery. We do know that when the land was sold to the Wilks sons in 1873, 1/4 acre was held out of the original 214 acre land grant. Perhaps this quarter acre holdout is a reference to the cemetery.

The 1870 census for Thomas Wilks includes Cornelius Edwards, age 27, working as black smith, Sarah Edwards, age 26, keeping house, and Warren Edwards, age 3, in addition to sons Madison, Newton, and Milton Wilks, aged 19, 16. and 14, respectively. Thomas is listed as a farmer and the boys as farm laborers. The three graves between the Cagle and Wilks rows are those of children. With Cornelius and Sarah in their prime child bearing years, and given the rate at which young children were lost in that era, these could be Edwards graves.

Poking deeper into the census records related to the adult Wilks children, I found a reference in the 1880 census to Mattie Wilks, one-year-old daughter of Newton and Mary Wilks. The 1890 census is missing and Mattie is not mentioned in the 1900 census, though she would have been 21 by this time and perhaps married. I’ve not found any reference to Mattie other than that one census entry. If Mattie died as a baby or young child, she could be lying in one of those unmarked graves. However, it would seem strange for her resting place to remain unmarked when the resting places of her little brothers are so beautifully marked.

In that same 1880 census record, the Newton Wilks household includes Tenny Martin, white, servant, age 7. Setting aside the heartache of imagining a seven year old servant, Tenny must be added to the list of possibilities. If she died young, an unmarked grave would seem consistent with the sad circumstances of her life.

Finally, we have the tragic case of Alvie Wilks. Alvie died at the age of 8 after being severely burned in an accident. Her mother also suffered severe burns while trying to save Alvie. The mother lived, but little Alvie succumbed. Alvie’s death certificate places her burial at the Wilks Cemetery but her grave was not among those marked. Either there is an error in her death certificate or she is one of our unidentified children. It stands to reason that she will be identified during the scientific assessment of the remains given the abundant family DNA available from well-marked close relatives disinterred, and the availability of living descendants of her family. It would be comforting to see her placed in a marked grave among her family when the remains are re-interred.

Story by Wanda Holmes Oliver.