In 1860, John William and Penelope Bonham were living in Mountain Township, Polk County, Arkansas. Included in their household were their children, Mary, Frances, Nancy, and John, as well as Salitha Bonham (age 64) and Mack Bonham (age 18). John was 37 and Penelope 30. John and Penelope had married in Tennessee in 1847. In 1866, their baby girl, Louisa, was laid to rest along side Charity Bonham (a woman of 53) in what has come to be known as the Bonham Cemetery in Fannin County. Charity and Louisa died one month apart and share a headstone. The headstone establishes Charity as the wife of David Bonham and Louisa as the daughter of John and Penelope. John & Penelope Bonham are buried in Smyrna Cemetery and their descendants are the source of the family references stated here. These are the facts we can verify.

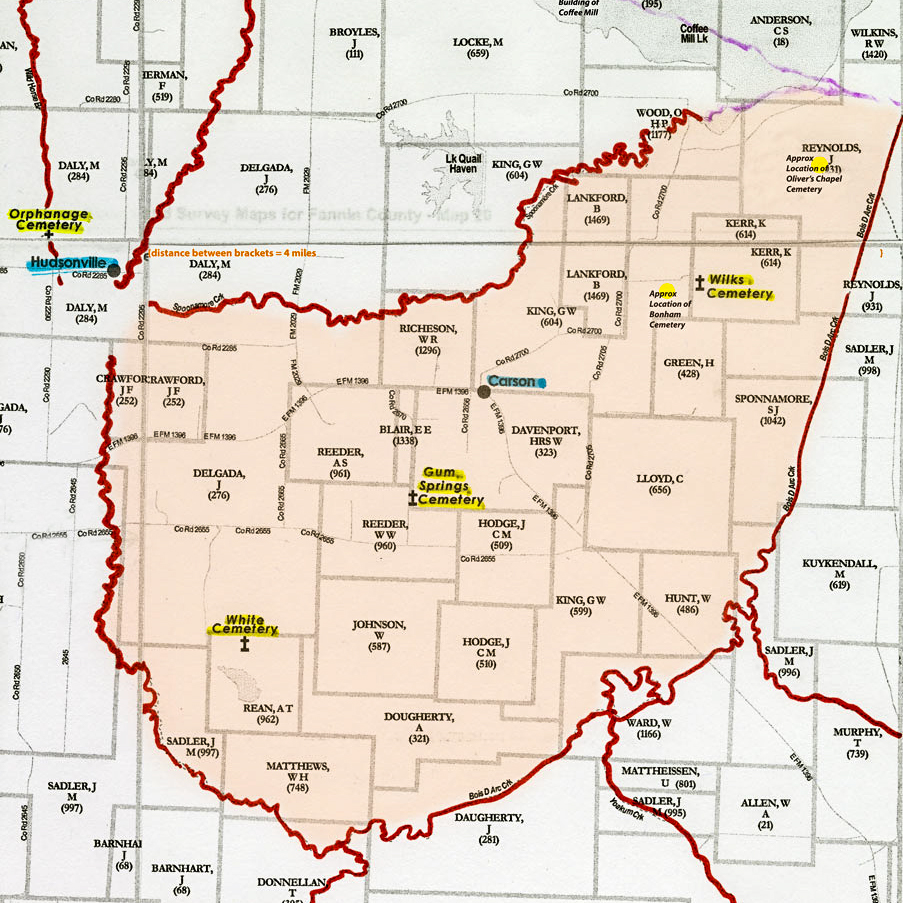

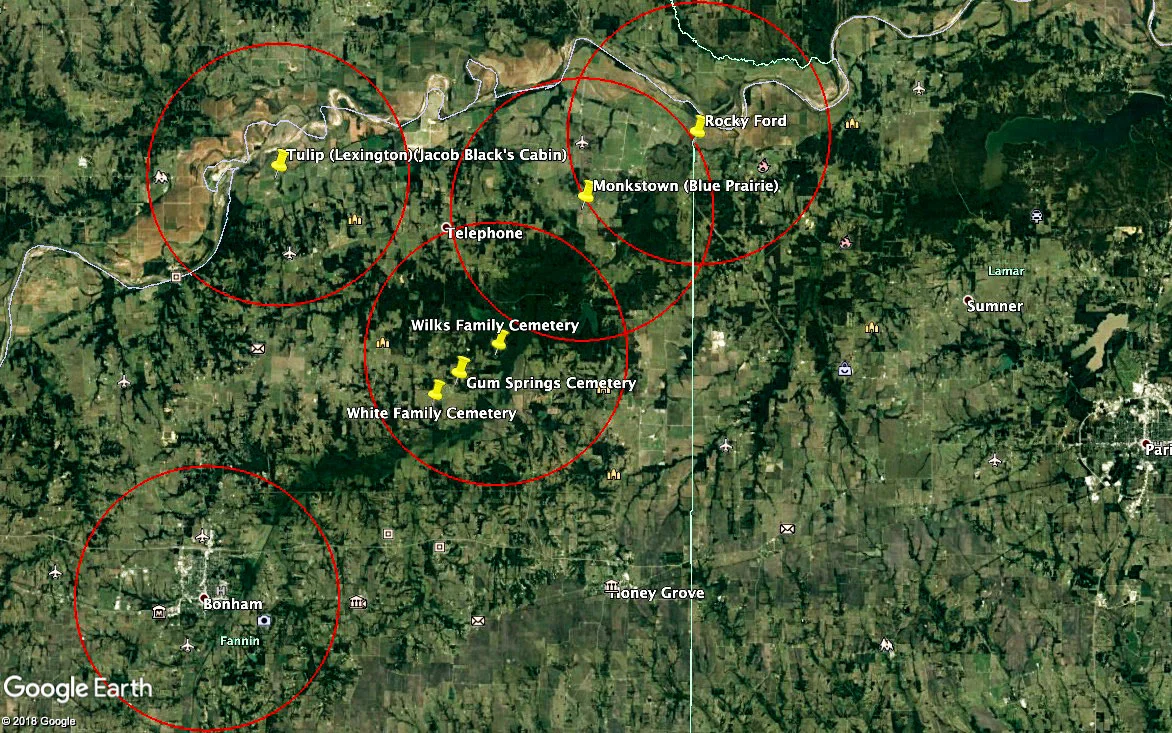

Family records indicate that the Bonhams left their home in Arkansas at the end of the Civil War and made their way via the Military Road to Fannin County where a sister of John’s was already living. This sister could be Casepha Bonham Cosner Allen, the 2nd wife of Wilson Bruce Allen, founder of Allen’s Chapel, though there are no definitive records establishing her relationship to John, and Casepha’s birthdate has been impossible to pin down. Some references place her birthdate in 1835, some in 1849. The first date places her in alignment as a possible sister to John, the second would make her more probably a daughter. In 1861, Sarah A. Bonham was married in Fannin County to James A. Wilson. She could also be the sister referred to. The family records indicate the sister was married to a doctor and James A. Wilson was a physician. These questions about the sister reflect the difficulty of pinning down information about John’s family. Was Salitha his mother? Mack and David his brothers? Charity’s birthdate precludes her being John’s mother, but John’s father was also named David, so Charity could be a step-mother, though she is generally accepted as a sister-in-law.

We are also left to wonder who was in the party that migrated from Arkansas to Texas. I cannot account for Salitha and Mack after the 1860 census. Mack, being in his prime, could easily have stayed behind or struck out on his own. Salitha would have been nearing 70. Did she make the journey? Had she died in Arkansas in the intervening years? Did she stay behind with Mack? Do she and Mack account for two of the unmarked graves in the Bonham Cemetery?

David and Charity’s story is another mystery. I have not been able to discover where they were living prior to Charity’s death here in Dec, 1865, despite scouring the census records for all Bonham’s in Arkansas and surrounding states for 1850 and 1860. Clearly Charity made the journey with the family from Arkansas. Did David come or had he died elsewhere? Could he be one of the unmarked graves? Though, if other members of the family were buried in the Bonham Cemetery why were there no markers for them, given the obvious love and care given to Charity’s and Louisa’s graves? Having exhausted all the clues and avenues that I could find or think of, I turned from the Bonham family to the question of what other families the unmarked graves might represent.

Local lore has it that the burials at the Bonham site were made by folks ‘passing through’. The burials themselves suggest the possibility of a group struck by catastrophe in what might be a temporary location. The graves are shallower and less sophisticated than those at the Wilks site, even though they are contempororary. It seemed clear that the migration from Arkansas might have been a group of several families traveling together, but it took a suggestion from a fellow history buff to give direction to that notion. He mentioned that traveling parties would often be made up of neighbors, the neighbors often being connected by marriage. His suggestion sent me back to the census records. Assuming that the census takers would work in an area, completing it before moving on to the next, I focused on the entries to either side of the Bonham’s in the 1860 Arkansas census. I searched the 1870 census for Fannin County for the surnames I found. I was hoping to find some of the people known to have been living near the Bonham’s in 1860 living in Fannin County in 1870, giving me a set of families to research further. Despite casting a wide net, I essentially struck out. I did find some of the same surnames, but none of the same individuals. For the moment, I am stymied and will have to let the mysteries be.

The grave of Charity & Louisa at the base of an enormous oak, decorated in the spring of 2018 by Ginger & Wanda, photo by Wanda Holmes Oliver.

Reinterment Site in Willow Wild Cemetery, photo by Wanda Holmes Oliver.

Story by Wanda Holmes Oliver.