As we wait for the first bit of scientific information to emerge from Dr. Whitely and her team about the remains removed from the Wilks and Bonham Cemeteries, I want to explore several lines of inquiry that could shed light on the unidentified remains found. These lines of inquiry include looking at the occupation of the land, the families on the surrounding properties, the early road systems in the area, and further details and gaps related to the information we have about the Cagle, Wllks, and Bonham families.

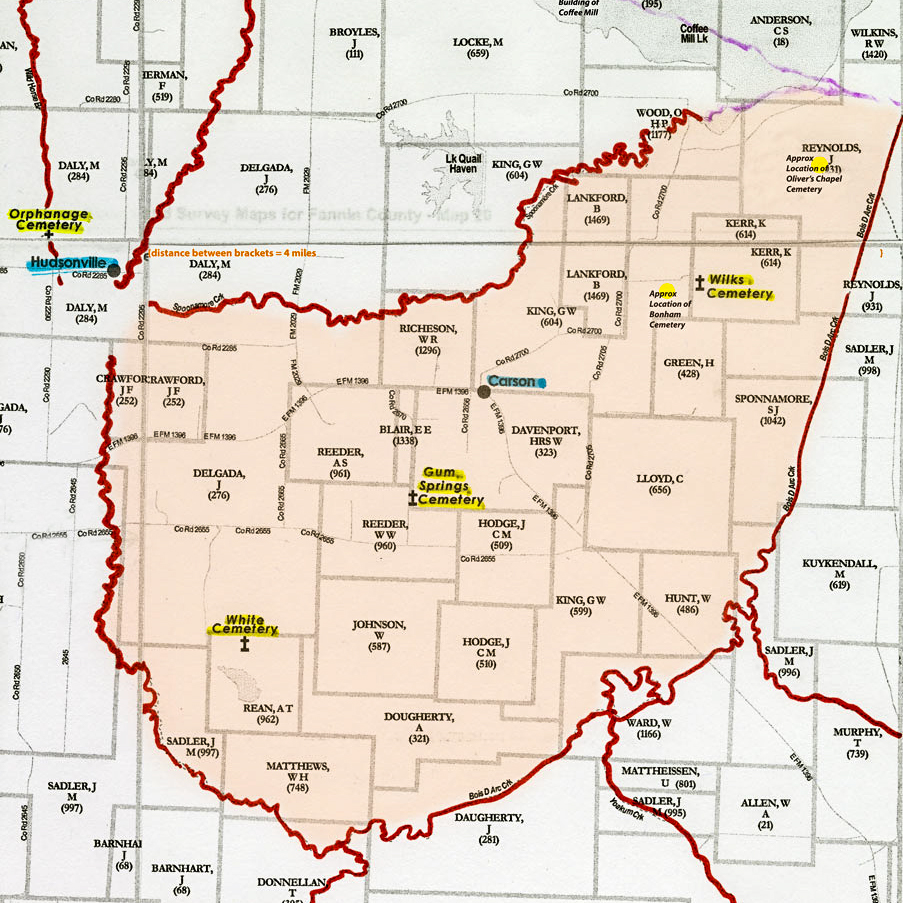

To begin that effort, I pulled all the known burials in Fannin County dating from 1838 to 1852 from the Fannin County GenWeb site. I used these dates because 1838 is the earliest recorded burial in Fannin County and Martin Cagle, the first fully documented burial in the Wilks & Bonham Cemeteries, was buried in 1852. The initial on-site assessment of the removal team was that the burials to the east of the Cagle row in the Wilks Cemetery were older graves, so my focus was on the period prior to Martin Cagle’s death. My intent was to map the ‘hotspots’ of early Fannin County settlement by locating where the known burials were, hoping that the pattern produced might provide clues as to these early Wilks Cemetery graves. The surnames of other early burials in the area would, I thought, provide good starting points for further research. I used the map of all known cemeteries in Fannin County from the GenWeb site as my starting point. The result for the northeastern part of the County is show below, with the current path of Bois d’Arc Creek highlighted.

There are a few scattered locations along Red River, and then a concentrated area south and east of Bois D’Arc Creek. The only known burials in the 1838-1852 time frame along the western side of Bois D’Arc Creek are those at the Wilks Cemetery itself (dark red dot on the map). The Wilks Cemetery stands conspicuously alone. Certainly there are burial grounds we will never know about where the only markers were wooden posts that have completely disappeared, but it seems likely these would be in proportion to the marked graves that have remained. And perhaps this pattern should not be surprising, illustrating early settlements spreading into the area from the more established communities to the east, overland and along the River.

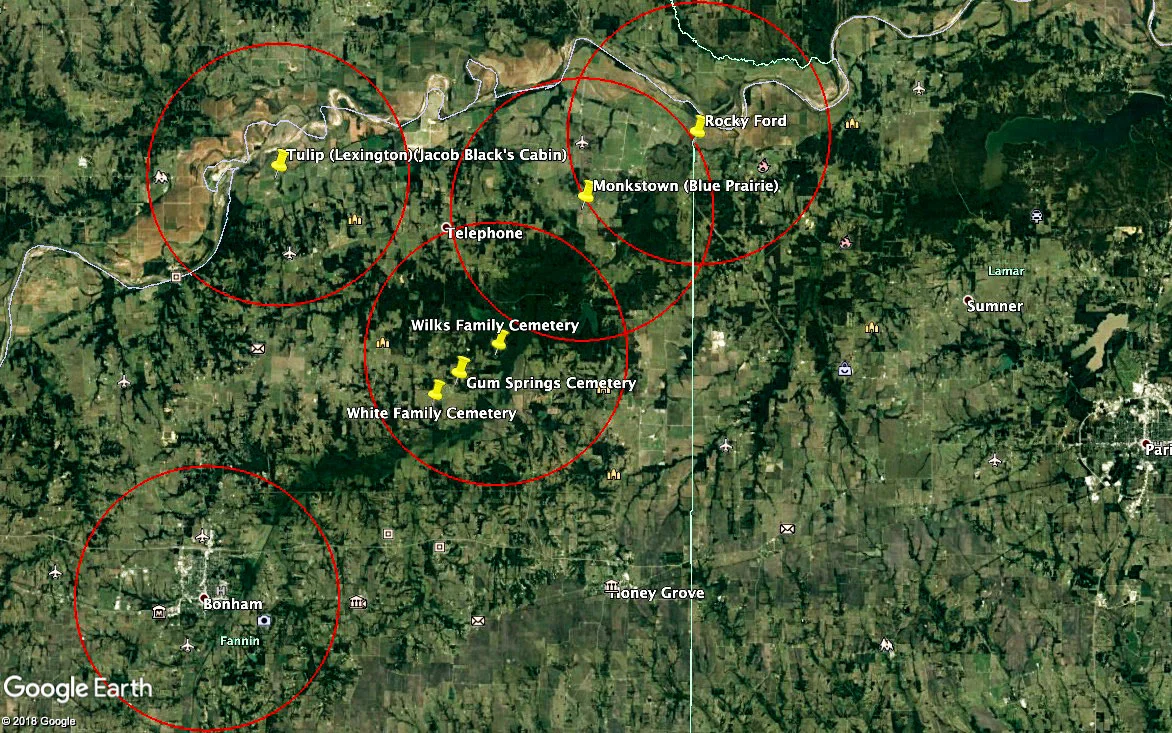

Studying this map, I began to think about how one would choose a burial ground for a loved one in frontier conditions. If there was a community cemetery in a given location, how wide an area was it likely to serve? What distance was considered nearby, what distance a long journey? To what extent would the area creeks limit travel in a time of few roads? These sorts of questions led me to the creation of another map.

Base map from “Texas Land Survey Maps for Fannin County”, by Gregory A. Boyd, J. D., used with permission of the publisher.

In this one, I highlighted the major creeks (in red) on a map of original land grant awardees, estimating the original course of the creeks prior to the creation of Coffee Mill Lake (in light purple). A ‘basin’ of sorts emerged (highlighted in pink) around the Wilks & Bonham cemeteries. The headright names provide a starting point for the original claimants of the land, and the creeks a reasonable boundary of an extended community.

In an attempt to put the ‘basin’ in context within the larger land area and the earliest settlements in Fannin County, and to explore the distances between them, I created a third map. Using the Google Earth app, I drew a five mile radius around key areas. I am told by old-timers from the Carson area, that even in the early 20th century a trip to Bonham was a two day affair in horse-drawn wagon. One day was dedicated to the drive into town and taking care of business. By then it was late, and folks would stay over night then start the journey home the next morning. Given the well established road system at that time, I felt safe in assuming that a five mile journey in an area of few roads would be a significant distance.

These maps have given me a lot to think about and a wealth of questions to pursue. They will guide and inform my research going forward as we piece together as much as we can of the story of the Unidentified.

Story by Wanda Holmes Oliver.