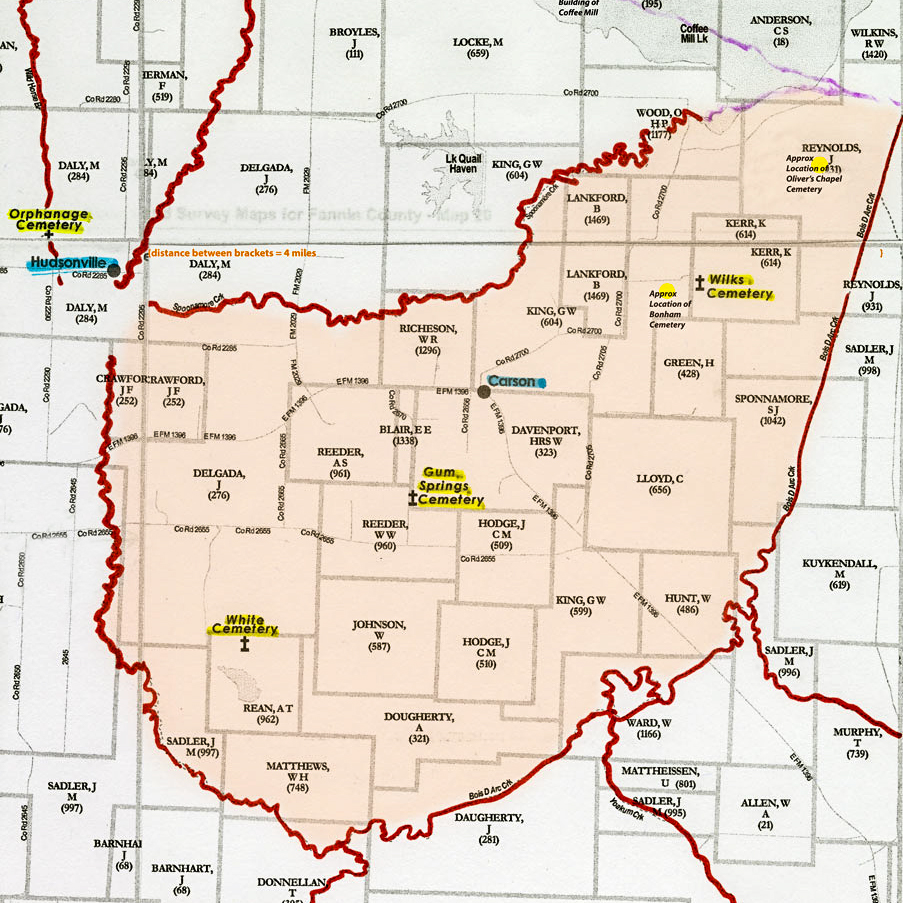

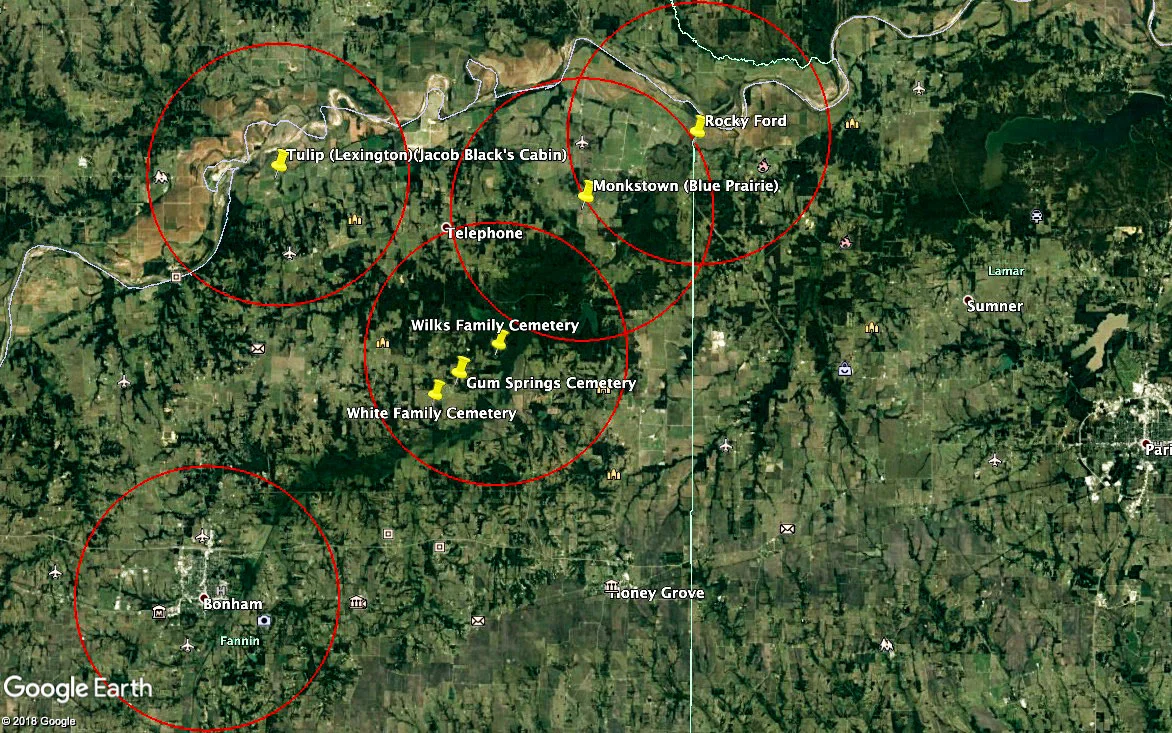

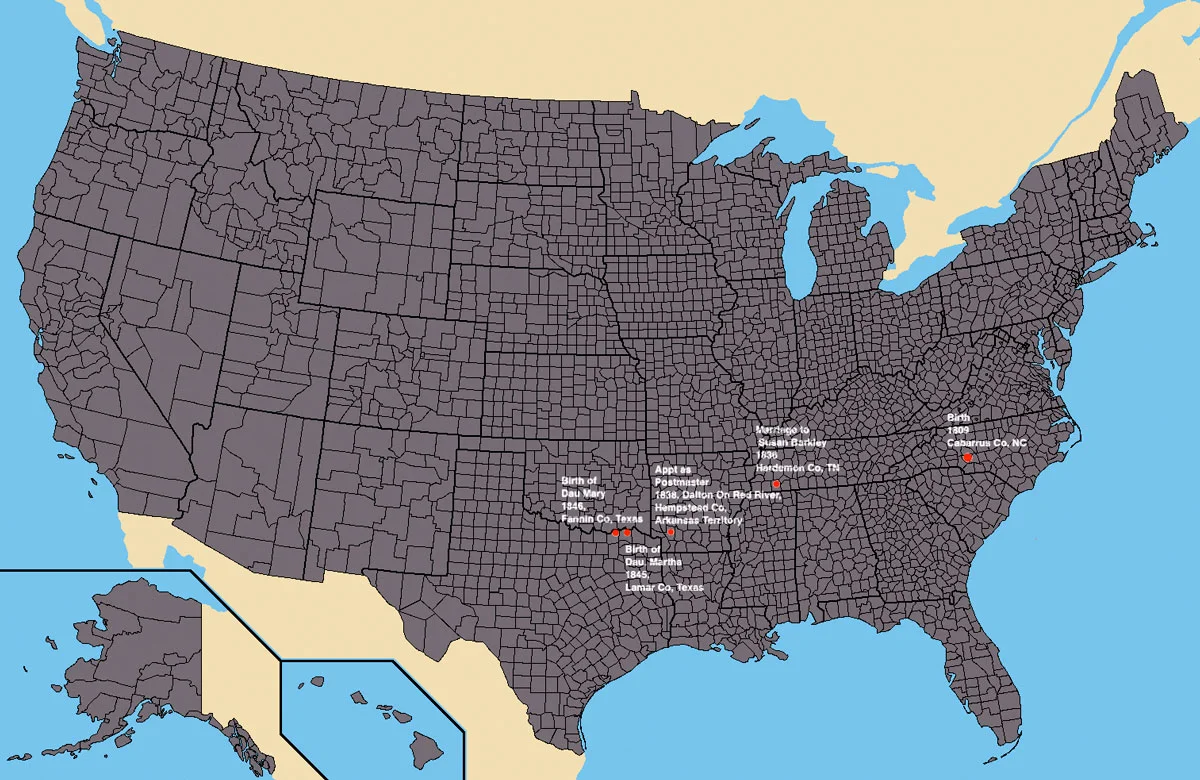

In researching the history of the land that became the Wilks Cemetery, and in trying to definitively identify the Cagle family members marked only with small stones bearing initials, I haunted the Fannin County Clerk’s office in the days before our current pandemic combing through deed and probate records. I’ve found several treasures there that I will be sharing here, and I look forward to being able to return to the stacks in search of more. Today’s post centers on the records I found regarding the estates of Susan, Robert, and Edward Cagle. These records established the fact of the early deaths without issue of Cagle sons Robert and Edward and confirmed that the land containing the Wilks Cemetery had remained in Cagle hands from 1846, when Martin Gaines Cagle first became responsible for the property taxes on the parcel, to 1873, when the parcel was sold to the Wilks. They are also interesting in what they tell of us notable property and property values in those years. The documents are transcribed in part below.

In Probate Book E, page 260, there is this (with some minor punctuation added for readability):

“Guardianship of the minors Mary C Cagle and John H Cagle. It is ordered by the court that Thomas C Hale be appointed guardianship of the persons and of property of John H Cagle and Mary C Cagle (the said Mary C having chosen in open court the said Thomas C Hale) and that he give Bond in the sum of $1000 (one thousand dollars) each and that letters issue.”

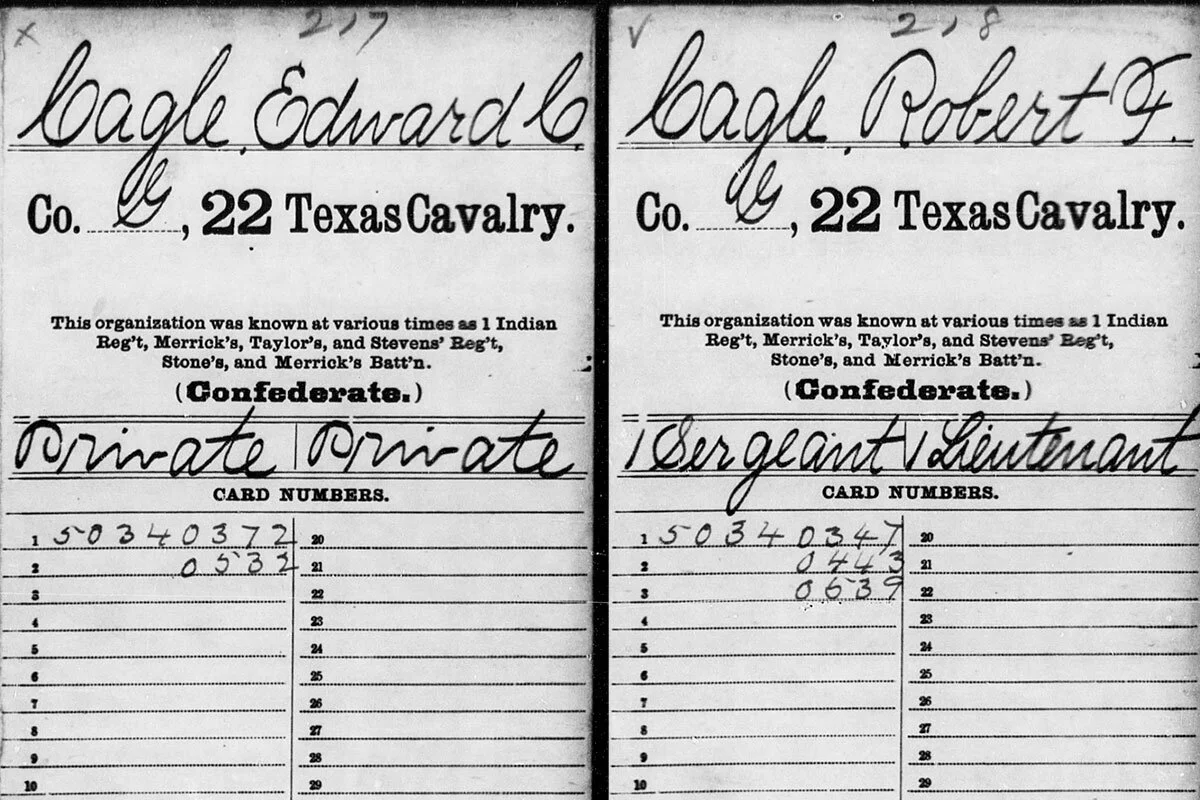

This entry is included in a list of several entries regarding guardianship issues before the County Court “at the Court House in the Town of Bonham on Monday the 24th day of November AD 1862”. Members of the Court present were W. A. Davis, R M. Cook, and Samie J. Galbraith. Susan Cagle, surviving parent of the minors had died in 1861. The elder Cagle sons, siblings to the minors, we now know from their Confederate Army military records had died earlier in 1862, Edward in March, and Robert in August. At the time of this court order, Mary was 16 years old and John 11.

In Probate Book E, page 421, we find the final report of Thomas C. Hale, administrator, to the Probate Court of Fannin County of the estates of Susan, Edward, and Robert Cagle (with minor punctuation and spelling added for readability).

“To the Hon. W A Davis, Chief Justice of Fannin County. Thomas C Hale, the administrator of the estates of Susan C Cagle, Edward C Cagle, and Robert Cagle, dec. would file herewith his final report for a settlement of said estates and ask to be discharged from all further liability as administrator. He states that there are but three heirs to said estates, viz. Frances D. Hale, the wife of this administrator, & the minors Mary C Cagle and John H Cagle, and that this administrator is their guardian (the two last mentioned). He asks that there be a partition and distribution of the property among said heirs or the same turned over to him as guardian for the two minor heirs - that is their portion of the property.”

The report goes on to list Susan Cagle’s property as a Sale Bill in the amount of $275, 1 yoke of oxen appraised at $50, 3 head of cattle valued at $20, 2 negroes valued at $400, 1 tract of land (214 acres) valued at $535, 1 tract of land (320 acres) valued at $640, and 1 hand saw & [?] valued at $20. The total listed is $1930, though when I add it up, I reach a sum of $1940.

Edward Cagle’s estate includes 7 head of cattle appraised at $42, 1 saw drawn knife and c[ase] valued at $5.25, 1 note on [?] of $10.50, 1 note on John Lankford of $15.00, and the estate of Susan Cagle in the amount of $1930, for a total of $2003.25

Against the estates of Susan and Edward, payments were made to settle the claims of J. J. Able ($50) and Dr Broom ($20), and to pay court costs of $30.

The only property listed for Robert Cagle is that passed on from his mother and brother, Thomas’ approach in settling the estates being to pass all of Susan’s property to Edward, all of Edward’s property to Robert, and then to pass Robert’s estate to the remaining three siblings.

An interesting aside is that in their military records, both Edward and Robert are listed as having enlisted with their own horses and saddles. It is curious that no horses are included in the estates. Robert died away from home and perhaps it would have been too much trouble to try to reclaim his personal effects in a time of war, but Edward died at home, apparently on furlough. Would he not have come home on horseback? Did the animals become the property of the Confederate Army when the boys enlisted?

Another interesting aside provided by the probate records is the value placed on the two slaves owned by the Cagles. In the tax records, beginning in 1846, the two are consistently valued at or near $1000. In November, 1864, as the estate is being settled, their value is listed as $400. Is this devaluation based on the declining fortunes of the Confederacy? Is it based on the advancing age of the two individuals? Why the sudden and dramatic difference? Even with that steep devaluation, however, each slave is worth the equivalent of 80 acres of land, illustrating the degree to which the economic base of the south was dependent on human chattel. It is shocking to confront the every day detail of human beings owned, traded, and handed down. This economic realization strikes to my core and bearing witness is painful.

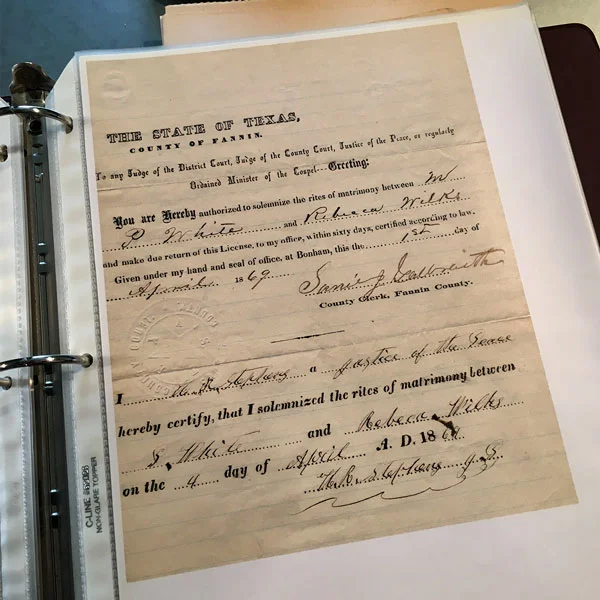

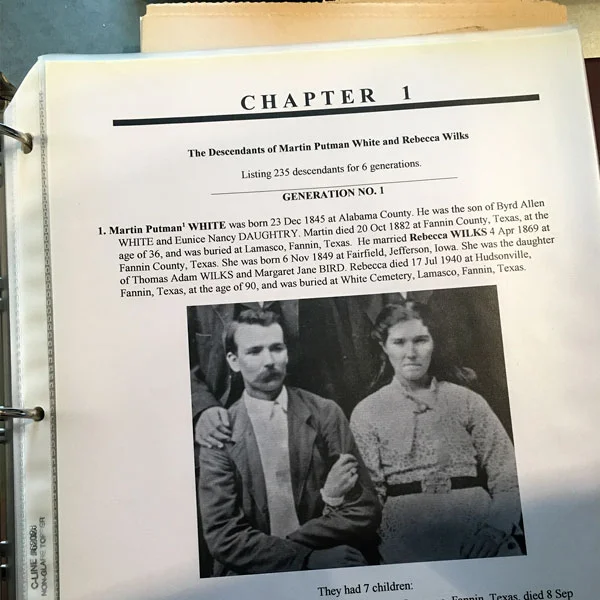

The final chapter in the story of the Cagle estates is the sale, in August of 1873, of the 214 acres containing the Wilks Cemetery site to Madison, Newton and Milton Wilks. In the sale, recorded in Book V of the Fannin County Deed records, page 492, only Frances and Mary (and their husbands) are listed as sellers. John has either relinquished his rights to his sisters or has passed away. The land, valued at $535 in 1864 is sold to the Wilks brothers for $412, a reduction in value of 23%, perhaps a further indication of the decline of fortunes after the war.

Copies of original documents on file at the Fannin County Clerk’s office.

Story by Wanda Oliver.